Featured News - Current News - Archived News - News Categories

In Respectful Memory - Erie County Poorhouse 1815 - 1913

by Multiple Author(s) See Article(s)372 Nameless Dead Re-Interment at Assumption Cemetery

372 Nameless Dead, Exhumed in 2012, Are Headed Back To The Grave

By Jay Tokasz | Published October 9, 2017

It will look and sound much like a traditional funeral: prayers, hymns, a Bible reading – even a bagpiper.

But when members of the University at Buffalo community gather on campus Wednesday to pay their respects, the ceremony will be unlike any other.

That's because the 372 men, women and children who will be remembered during the service are still unknown by name.

They died more than 100 years ago and were buried in unmarked graves on the grounds of the Erie County Almshouse.

Their remains were exhumed in 2012 to make way for construction on UB's South Campus, which is situated on the old county poorhouse property. Now, after years of research to try to determine the identities of the dead, the remains are going back into the ground.

Assumption Cemetery on Grand Island will become the new final resting place for the remains.

"They've been above the ground a long time, and they deserve to go back," said Douglas Perrelli, UB clinical assistant professor who oversaw the exhumation. "Certainly the intent is not to disturb these people again."

Researchers took pains to keep all the individual remains separate, from excavation through the entire research process. For burial, each individual's remains were placed into a non-biodegradable pouch. Some of the remains consisted of full skeletons, while others were small bits of bone, no bigger than a dime. The 372 individually-tagged pouches will be put inside eight caskets and buried in four plots donated by the cemetery.

"Even though we don't know them individually, they will be cared for in eternity," said Carmen Colao, diocesan director of Catholic Cemeteries, which owns and operates Assumption Cemetery.

Researchers estimate as many as 3,000 people could have been buried at the old poorhouse cemetery. Assumption Cemetery has room for more remains, if future construction projects at UB lead to the discovery of other coffins. The cemetery set aside a quarter acre, or up to 50 burial plots, for poorhouse remains.

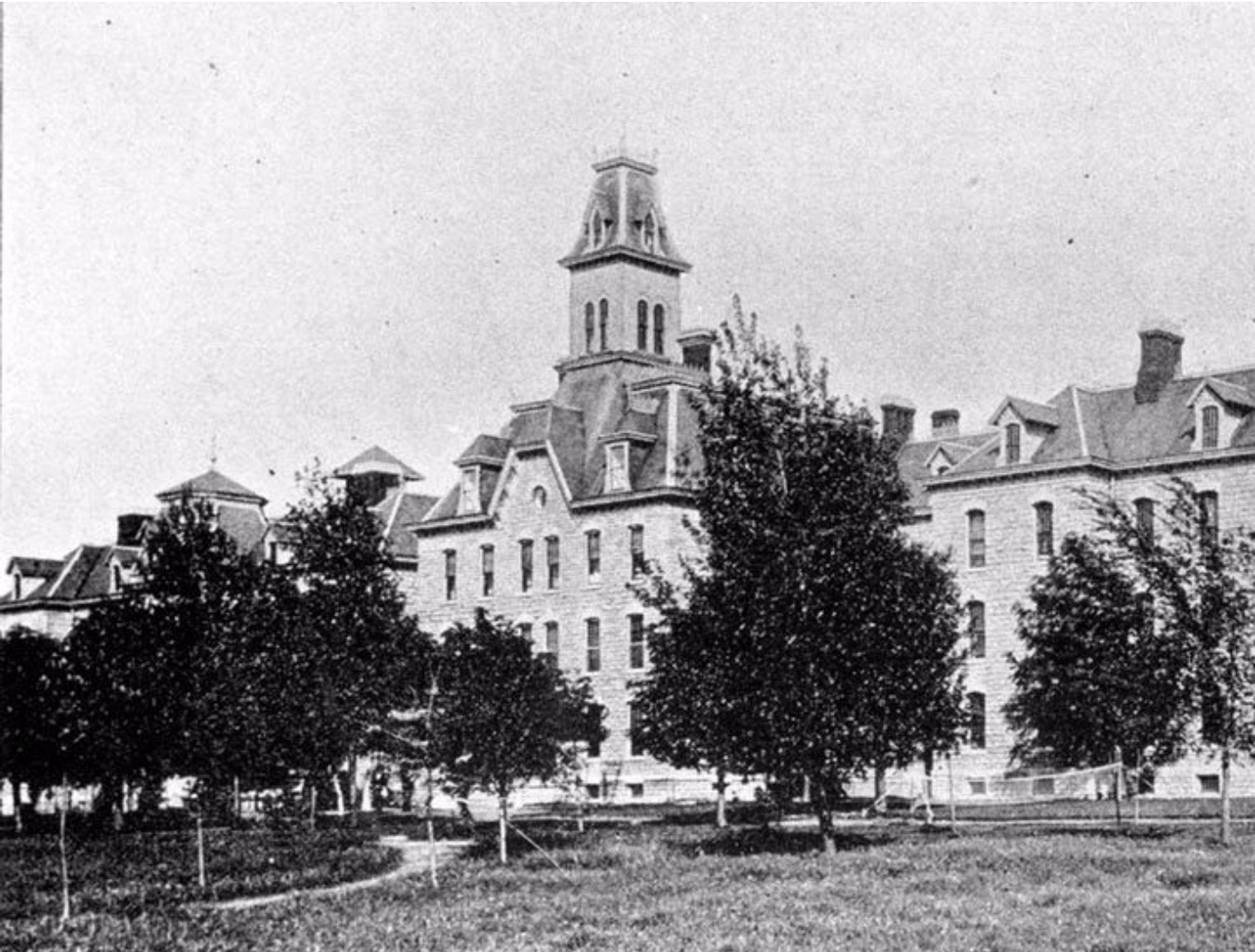

The former Erie County Almshouse, now part of Hayes Hall at UB's South Campus.

A monument donated by Stone Art Memorial marks the re-interment area at the cemetery. It reads: "In respectful memory of the men, women and children of the Erie County Poorhouse 1851-1913. A temporary shelter for some, a much needed home for others. The remains of the deceased in the former poorhouse cemetery were moved to this site from the grounds of what is now the University at Buffalo South Campus. May this permanent resting place bring the peace they sought in life."

Construction crews began uncovering grave sites in 2008 during a lighting project along Bailey Avenue. More remains were found in 2012, as crews replaced sewer lines near the Michael Road entrance to the South Campus.

It was then that the university received a State Supreme Court order allowing for the exhumation of the remains by a team of trained UB archaeologists and physical anthropologists.

Researchers found names for people who lived, died and were buried on the poorhouse grounds, but they couldn't definitively match names to the 372 remains due to inadequate record keeping at the poorhouse.

Poorhouse administrators recorded numbers in a ledger book that would have identified where they buried the dead. The numbers were also marked on stakes pounded into a grave site. But year after year, they reused the same numbers, making it impossible for researchers to match numbers to remains.

"When the ground froze, the grave digger would go pull up all the stakes and then use them again next year," said Joyce E. Sirianni, professor of anthropology.

A black-and-white photograph of the Erie County Almshouse and Hospital, before it became Hayes Hall. (University Archives Photograph Collection/UA 20DD)

Though they were unable to attach names to the remains, researchers learned plenty about the people buried in the poorhouse cemetery. Not all were paupers. Some had enough money to get dentures and must have fallen on hard times. At least 60 remains were those of infants. Many of the bones showed evidence of trauma. "Many individuals had fractures, healed bones, indicating it was pretty rough," Sirianni said.

Sirianni oversaw the work of four doctoral students and two postdoctoral researchers who studied the bones inside a laboratory for more than a year.

Many of the people who ended up at the poorhouse, which was located amid fields, far outside the urban core of Buffalo at the time, were recent immigrants from Ireland or Germany. Poorhouses provided a roof overhead and food for people who had no other options. In exchange, they were required to work on the poorhouse farm. A stay at the poorhouse usually was temporary, and many residents were able to get their financial footing and move on.

"Buffalo was a growing city. These are the people who helped build the city with their hands and their backs," Sirianni said.

Researchers grew to admire the people they were studying – even if they never knew their names.

"We all feel the sense that they're our friends. We got to know them quite well," she said.

Students and faculty will serve as pallbearers at the non-denominational funeral.

It will include a reading from the Old Testament Book of Ezekiel, a passage known as "The Valley of Dry Bones," and bagpipe playing of "Going Home."

Monsignor J. Patrick Keleher, director and campus minister for the UB Newman Center, will co-officiate at the service with Sirianni, who is a Presbyterian minister in addition to being a professor.

"I've never done anything like it, but we'll do it with the same care and respect as with one person," Keleher said. "It will be quite wonderful, I think – simple, but dignified."

University officials reached out last spring to the Erie Niagara Funeral Directors Association for guidance on how to go about properly re-interring the remains. The association helped apply for burial permits with the state and provided direction on how to make sure individual remains were kept separate from each other.

"This is what we do every day. We bury the dead with dignity and respect, whether there are relatives or no relatives. Everybody deserves a proper burial," said Gerald Gentile, longtime funeral director and the association's president.

________________________________________________________________________

After A Decade of Research, UB Anthropologists to Memorialize Remains

By SARAH CROWLEY | Published October 8, 2017

The lives of those buried in the Erie County Poorhouse Cemetery from the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century will be commemorated on Oct. 11 at 11 a.m. in the Newman Center. The ceremony culminates nearly a decade’s worth of research into the remains of 372 persons buried in the cemetery on Bailey Avenue.

A group of UB anthropologists headed by Doug Perrelli, clinical assistant professor and director of UB’s nonprofit Archaeological Survey and Joyce E. Sirianni, SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor, studied the remains of the people buried in the Poorhouse Cemetary for the past nine years.

The community-wide effort produced an immense body of research; several students received Ph.Ds and master's degrees through this project, according to a UB news release.

The project began in 2008 when a group of construction workers discovered human remains from the former Erie County Poorhouse, which was situated on the border of Bailey Avenue, now part of UB’s South Campus. The poorhouse was refuge to many of Buffalo’s poor and middle class families at various times from the late nineteenth to early twentieth century.

Perrelli and Sirianni lead the task of disinterring the human remains and monitoring construction in the area to ensure respectful, complete removal of all individuals’ remains. They then provided public outreach, from student engagement to new courses, book chapters and symposiums.

From the onset of the project, Perelli and Sirianni’s chief goal was to restore identity to these people that had been lost and forgotten over time.

“We demanded they be respected and that we not forget them,” Sirianni said. “They were kind of forgotten for a long time. The right thing to do when you remove them from their graves is to rebury them with the dignity that they deserve.”

They were not able to name the bodies as they originally hoped, but the team was able to produce biological profiles of the deceased, looking at their age, gender and ancestry. Their work included skeletal analysis, demographics, causes of death and disease identification.

In some cases, the anthropologists were able to determine religious affiliation and occupation based on various markers.

Sirianni said this opportunity is unlike any other.

“It’s very rare that you have that many individuals and we knew quite a bit about them in terms of this great historical record but it doesn’t tell you anything about these 372 folks,” Sirianni said. “They’re all unmarked graves.”

This project was helped further by a group of community experts which included the Erie Niagara Funeral Directors Association, Stone Art Memorial, Catholic Cemeteries of the Diocese of Buffalo, the Wilbert Vault Company and the New York State Division of Cemeteries.

A funeral procession will leave the Newman Center at UB, 495 Skinnersville Road, Amherst and will proceed directly to a private burial service at 1 p.m. at Assumption Cemetery in Grand Island, NY.

© 2017 Catholic Cemeteries | 716.873.6500 | Site Map | Login